Tejpaul Bhatia thought he was going to work for Google for the rest of his life. After 10 years as a serial entrepreneur, Bhatia was ready for a steady job once his first child was born. He spent three years as a startup ecosystem manager at the tech giant, before becoming an advisor on Google’s remote work policy when the pandemic began. Then, about a year later, came a call from Axiom Space with a job offer.

“It took the one job in the world that would get me to leave Google,” Bhatia said.

Now, Bhatia has started a new role as Axiom’s chief revenue officer, overseeing revenue generation and monetization strategy for the company. Axiom is one of the bigger players in the private space race, and its partners include SpaceX, Airbus, Boeing, and NASA, which awarded the company $140 million to build modules to connect to the International Space Station.

Axiom’s ultimate goal is rather lofty: the company plans to build the world’s first commercial space station. The ISS will be out of commission by the end of the decade, and Axiom’s space stations could potentially replace the 23-year old station.

But before launching a space station, the company plans to send astronauts to the ISS as soon as early next year. And with a renewed interest in space travel, the world will likely be watching as Axiom makes its first launch — something Bhatia is looking forward to.

Bhatia spoke about his role at Axiom, why our fascination with space never really went away, and the lessons he learned from a decade of entrepreneurship.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Business of Business: I would just like to hear about Axiom Space and your role there now.

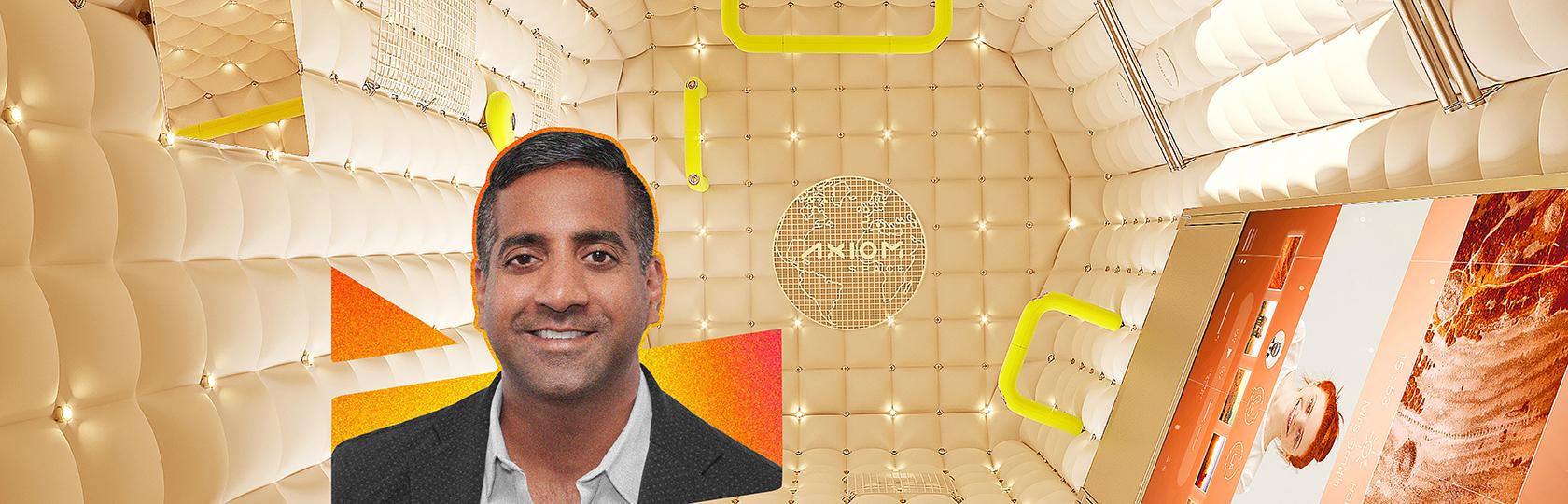

Tejpaul Bhatia: Sure. So I joined Axiom about a month ago, as chief revenue officer. I have been friends with Axiom for about four years. I'll tell you a little bit later about how I got to know them and how I got involved with them. But primarily, what Axiom is doing is building the world's first commercial space station. And you see the rendering behind me. And it is a crazy idea, sounds crazy, and it is crazy.

When I first heard it, I was immediately enamored with it. And as I got to know the company, what it means for the space station to go up and build a business around it, I realized that while it literally is mind blowingly impossible to put a space station in orbit, it's also very hard to build a startup. It's also very hard to develop a market that really has no precedents. And this is not to belittle what it takes to put a space station out. But our CEO and founder and many of the employees are aerospace people that put the International Space Station up [into orbit].

And our company is starting to send missions up early next year 2022, to the International Space Station, with civilians and former professional astronauts as mission commanders. And what you'll start seeing several times a year is flights going up, civilians going up, and modules going up, where we are actually adding on to the International Space Station. So what you see behind me is the final product. Several years down the line, the ISS might be decommissioned, and it will disconnect and go to where all space stations go after they've lived a good life. And we will be a free-standing commercial structure in orbit.

That is absolutely fascinating. I can see why you were enamored with it. So several years down the line. When can we expect an Axiom station up there?

In a handful of years, you know, we're not talking a crazy, wild future. I think this is also another challenge, where you look at projects, ideas like the International Space Station, these huge infrastructure, science, and multinational collaboration efforts. That doesn't typically fit the venture capital model, even if you couldn't make it fit the venture capital model to venture capital time horizons.

“July was amazing for human space travel. In a matter of weeks, we doubled the number of civilians that have been to space.”

I actually first met Axiom four years ago. I was an entrepreneur in residence at Citi Ventures and I saw their pitch for their Series A, and I thought this was phenomenal. I brought them into Citi and really got to know them and saw what they were doing. And then when they got the contract with NASA, few years later I said, "Oh, that is a real step forward, it's a real advantage."

Like I said, there's only a few people in the world who have ever put a space station up and our CEO is one of them. And if there's anybody I’d follow to do it, it's him. Where my role comes in and where the challenge comes in, is how do you turn that into commercial business? And how do you do it in a timeframe where our other founders and leadership members have raised outside capital and venture capital? This is a private commercial company, and how do you do it in a timeframe, and with a narrative that, on the tech side, we're all very used to for the last 30 years. You look at the top five largest companies by market cap right now. And they're all tech companies, all venture-backed companies, all born and bred within our lifetimes. It's not like the world was back in the 90s, where it was large institutional oil and gas, automotive financial companies that have been around for hundreds of years. These are brand new companies. And that's where I see the space industry going over the next several decades.

Why do you think there's such a renewed interest in space travel? It seems as if the interest waned and picked up again in recent years with Bezos, Branson, and Musk going up into space.

I will correct you a little, when I say correct you, I don't mean this by fact, it's by perspective. I don't think the interest was ever lost. You speak to anybody who is fascinated by space, they've never lost their interest, right? Whatever the media cycle, that doesn't change my childhood dreams, right? It doesn't change how the last four weeks of this company, even the fact that we're having this conversation, just seemed surreal.

And as you mentioned, Bezos and Branson, July was amazing for human space travel. In a matter of weeks, we doubled the number of civilians that have been to space. We can argue what space means, were they in orbit, did they go to the station, where they past the Kármán line, who cares? It was amazing to watch. The whole world was watching and for the business I'm in, and it just sets us up so well that this is real. The fact that the founders went up, and I know there's varying feelings on social media for that.

It reminds me of a story. I don't know how true it is. But you know, people were afraid of light bulbs. So what Edison did was a parade in Manhattan. People were wearing lights in the middle of the night. If you look at Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic, they've been trying for a long time. Virgin Galactic has been telling the story for a very long time. These are huge projects that require iteration. And unfortunately, it's not like a tech startup where version 0.1 of your app doesn't look good.

I was a startup founder for 10 years. Three different companies all venture backed all this amount of scale, and we use words like “crash,” we use words like “survival.” We better be around or we're gonna die, and I realize, yes, this is a startup, but the people that are going up in January for Axiom are my friends. I just was like, Oh, well, let me let me change my frame of reference. Because when we're talking about what we're doing, this is very different from the startups I've worked on before.

There is actual risk taking, you're risking your life attempting to go into space. As chief revenue officer, you're not going up to space anytime soon. What are your greatest challenges in your role?

So I mentioned to you that I'd met the company four years ago, tracked them, became friends with them, and I ended up making an angel investment about a year and a half ago. First investment I ever made. Even though I was a startup founder for many years, and I had many investors that came along the ride with me, for those three companies, I had never personally made an investment. I decided I want to start investing.

And a few months later, I get a call from the leadership team, a friend of mine, who actually brought me into the round and said, Hey, can you help us? Can you help advise on business development, ecosystem management? That was kind of my area of expertise. In my previous job, I was at Google for almost four years, leading ecosystem management strategies as a way to drive business. I said, "Okay, I'm used to working with startup founders, but, you know, private astronauts going up to space, maybe there's a play here." And in advising them, the CEO came to me and said, "Hey, I've been thinking about this role for chief revenue officer. Have you heard of it? "

“I was done. I didn't want to be a startup founder anymore. It is a very hard career...Going through it], it was very difficult. I was exhausted, I was beat up, I was broken.”

[I said] I'm not sure who that would be in the aerospace industry. Because from a market development from a commercialization standpoint, it's always been government driven, maybe a little communications driven. So in terms of what Axiom is doing, trying to do for human spaceflight, and civilizations in space, I just don't know who that person would be. And the CEO stopped, he’s like, "Oh, sorry. Maybe I wasn't being clear. I wanted to see if you wanted that role." So my mind exploded, and I couldn't even speak. I said, "Okay, let's talk through it. I realized why it was a brilliant move to bring me on." I don't mean to say I'm a [particularly] brilliant brain. But the thought of bringing someone like me, someone from Google, with startup experience and some venture experience at Citi Ventures [was brilliant]. We are doing two things. Yes, it's revenue generation, but it is monetization strategy, revenue generation for how we build a company over the next several years, but monetization strategy for what this new market is. What are these business models? I do see several analogies to the last wave of kind of hyper growth in technology. But I also strongly believe there's many things we don't even know till we're out there living there, working there. That's going to be an entirely new economy.

You talked about being an entrepreneur and startup founder. What made you want to get out of the role of founder and join a larger company like Google?

I'll give you an excuse and then I'll give you a reason. The excuse was my son was born. He's five years old now. It's almost five years to that date. I decided I didn't want to be a startup founder a few months after my son was born. And why say it's an excuse? First, I don't want to blame my family for the reason I'm not a startup founder, I don't think my wiring changed. I don't think, "Oh, now I’m a dad, I can't be a startup founder." But it was the perfect reason for me to really think about what I need in my life, who I want to be in my life, where I want to be as a family person.

But the real reason was, I was done. I didn't want to be a startup founder anymore. It is a very hard career. I think about my choices, when I became a startup founder and stayed one for 10 years, I had no clue what I was getting into. I don't think even if I could go back in time and tell myself, "Hey, it's going to be really hard, there's going to be a very steep emotional toll on your life," I still probably would have done it. You know, the rewarding side of it definitely outweighs the cost side of it. I don't mean financially, I mean life experience. I literally wouldn't be here today at this company, if it weren't for that, you know, and there's no way I could have known this going through it. But going through it, it was very difficult. I was exhausted, I was beat up, I was broken. And my wife, my life partner throughout this whole thing, was extremely supportive, and extremely aware of what the career choice I made put me through. I didn't think it was fair to bring my son into that. Right, he has no choice in that. So I decided I'm stepping away. And, you know, I'll go back into the workforce. And that was a very difficult pill to swallow.

“The greatest lessons I've learned are understanding that you don't know what you're doing. Being self aware of that. Everything is a problem to solve.”

And then Google reached out and they had this opportunity to join them as a startup ecosystem manager, to help represent Google out to the startup world. And Google was a phenomenal company. I mean, I loved every second of working there. You know, those myths as the greatest company in the world were true, they're like, it's even beyond that.

A friend asked me, how long will you be at Google? I said, probably forever, like this a great place to be. And then I see my friend, you know, a month later and I'm like, "I'm leaving." And he's like, "What?" And I said, "It took the one job in the world that would get me to leave Google." It happened, you know, it's like a no brainer, I'll take it. I'm really grateful for my employment experiences. I think kind of that cross between my startup experience and my professional experience just aligns so perfectly for this role in something that I thought I would not be able to add value to, right? This is aerospace, what do I know, I'm not a rocket scientist, I'm not a billionaire. I very quickly realized that there's a lot of white space there. And if we're going to build a commercial space economy, industry, and we're going to move humanity forward off the planet, it takes everyone, right? So it's also a narrative that I couldn't work in this industry. And it's very clear that you need people on the ground to run things that every company needs, and plenty of other companies have a chief revenue officer.

What have been your greatest lessons that you've learned as a founder that you can impart?

The greatest lessons I've learned are understanding that you don't know what you're doing. Being self aware of that. Everything is a problem to solve. So getting good at solving problems is much better than just knowing certain skills. I forget who said the quote, but "if you think you can't, you're right."

It's very much about being your own best advocate, your own coach, being in tune with yourself. I think that makes you better. Better emotionally aware of how everyone else is doing. But if you have to take care of yourself, and it's human nature, and it's very easy to fall down a path where you're very hard on yourself, I think you need to treat yourself really well. The lesson that comes out of that is knowing yourself, being confident in who you are and being okay with saying I don't know. I would much rather my team members tell me "I don't know" than give me a made up answer or no answer. Like, let's figure it out.