Ongoing shortages of consumer goods, from automobiles to cream cheese, have ended the era of “invisible” supply chains. We are now forced to consider the intricate logistical networks responsible for filling the shelves in our local stores. And we’ve been made painfully aware of how fragile these systems are in the face of global pandemics, wars, and various acts of God.

This is especially true of supply chains that converge at a limited number of sources, as is often the case with raw materials and industrial components. Many of the most vital ingredients of world manufacturing originate from just a handful of mines and facilities, sometimes concentrated within the borders of a single country.

The status quo is not exactly conducive to ensuring global economic stability. Dominant exporters can easily leverage their control of important resources as bargaining chips in trade negotiations. It also makes global supply chains vulnerable to natural and manmade shocks that may befall those nations.

Although the issue has recently become a strategic priority for policymakers and the U.S is starting to make moves to reorganize the supply chains of some strategic commodities, this is a slow process that may take years.

“You can't just rip up the supply chains and move them somewhere else.” Christopher Mims, a Wall Street Journal columnist and author of a book on supply chains recently told GQ. It’s not just the natural concentration of resources creating issues, Mims noted that technological capabilities and expertise are currently concentrated in specific locations.

Since our undiversified supply chains are likely to keep causing us all problems, it’s time we start to pay attention. Here, we look at some important goods with supply chains that hinge on just one or two major exporters and explain the industries they’re most likely to impact.

Lithium (Batteries):

Mines in Australia and Chile are responsible for the vast majority of the world’s lithium production at 55% and 26%, respectively. The two countries are home to two-thirds of the world’s reserves.

If either country becomes unable or unwilling to continue to supply the element, it will have serious implications for all things battery powered. About three-quarters of extracted lithium goes into battery production, and this is likely to increase as the electric car boom continues. In the short run, supply issues in Australia or Chile could therefore severely impede electric vehicle production. Although multiple countries possess large reserves of the metal, building the mining infrastructure would take time and resources.

Cobalt (Electric Vehicles):

More than two thirds of the world’s cobalt production takes place in the Democratic Republic of Congo, home to over 50% of global reserves. The country does not have a reputation for political stability. Its current president came to power in 2019 by means of voter suppression and political violence. Chinese companies used the government’s weakness and corruption to establish dominance in the DRC’s cobalt mining industry. Many of the mines under their control are notorious for their abysmal working conditions.

Like lithium, it is a key ingredient in batteries, preventing them from overheating and averting potential explosions. The material’s concentration in the DRC has already caused some headaches for the electric vehicle industry. Tesla secured access to 4%of the global cobalt supply in a 2020 deal with the Congolese subsidiary of Glencore, a Swiss-owned mining company. The EV manufacturer aims to eventually eschew the blue metal from its battery design, due to its price volatility and the human rights abuses associated with its extraction.

Neon (Computer Chips):

The Russian-Ukrainian war is just about the worst thing that could have happened to the global supply of neon, a gas that is essential to semiconductor manufacturing. Ukrainian companies happen to produce over half of the world’s purified neon – and two of them have ceased operations in recent weeks. Both are located in Mariupol, a port city which is currently under siege by the Russian military. Ukraine’s neon producers source the unpurified version of the gas from Russia, where it forms as a byproduct of steel manufacturing.

Neon is used in lasers that print patterns on the silicon in computer chips, a process known as lithography. Supply issues with the gas will likely exacerbate the ongoing global microchip shortage, further driving up prices for new cars and consumer electronics.

Uranium (Nuclear Power):

Over 40% of the world’s uranium comes from the mines of Kazakhstan. The top three producers, which also include Australia and Canada, currently account for over two-thirds of global supply. Kazakhstan is not a democracy, and its resources are largely controlled by a small minority of governing elites. Any political instability, such as the wave of civil unrest that rocked the country earlier this year, can threaten the continuity of the global Uranium supply.

Uranium is used as fuel for nuclear power, which is considered to be a cleaner source of energy than coal and natural gas. Nuclear power plants generate about 10% of the world's electricity. They are the second largest source of low-carbon power (after hydroelectric plants).

Steel (Construction):

China is by far the world’s leading steel producer, with its factories churning out over half of global output. Steel, of course, is necessary to keep a whole host of industries going from construction to car manufacturing.

The country is also the biggest consumer of refined steel. This is in part due to the fact that high labor costs and stringent environmental regulations render steel production in high-income democracies uncompetitive. The industry is known for its damaging environmental impacts, and the Chinese government issued a directive in 2021 aimed at lowering steel production in order to curb pollution. Still, China hasn’t been hesitant to try to take advantage of its position as the top producer. The Chinese steel industry has been accused of dumping, a practice that involves the selling of goods at artificially low prices to stave off competition. The EU has imposed tariffs on Chinese steel in a retaliatory measure against the practice, helping its own producers compete on the domestic market.

Rare earth metals (Batteries):

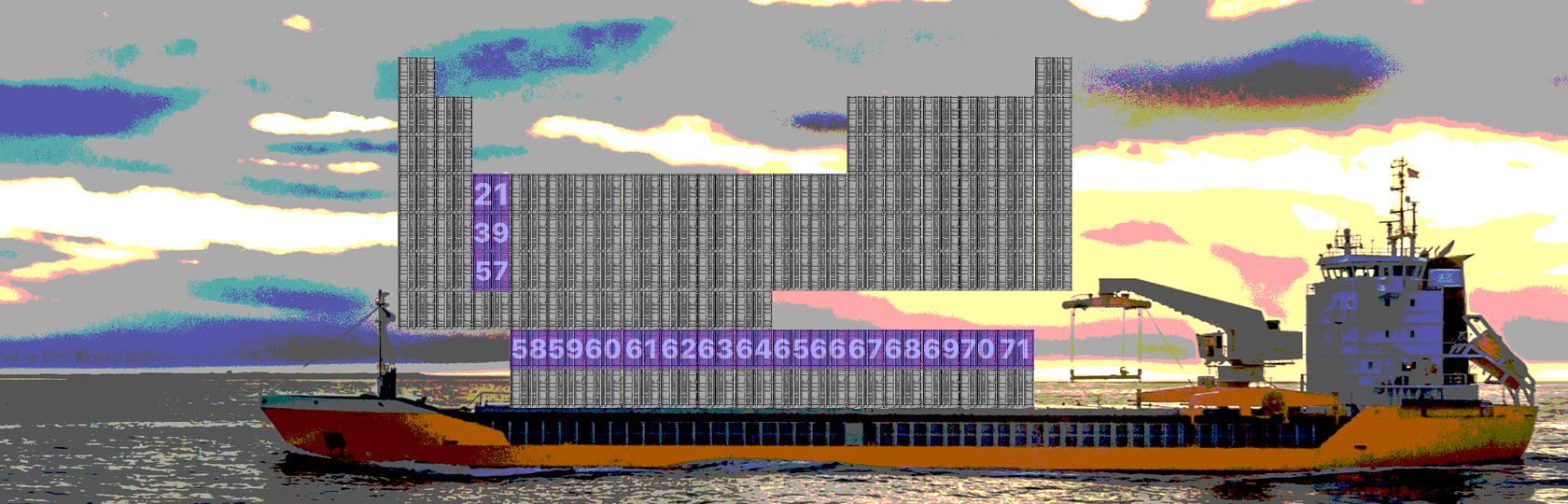

China dominates in rare earth metals production, as the country is responsible for 58% of global output. Rare earths are a group of seventeen metals valued for their conductive and magnetic properties, which makes them essential to electric battery manufacturing.

In a move to consolidate China’s rare earths industry, the government approved a merger between the three largest mining companies. The new entity has outsized market power through its influence on worldwide price formation for the commodity. Though the United States has aspirations to become a leader in electric vehicle production, which would require lots of electric batteries, it currently mines just 16% of the world’s rare earths.The senate recently introduced bipartisan legislation to wean the U.S off its dependence on Chinese rare earths and begin building a strategic stockpile.

Silicon (Semiconductors):

China is the world’s largest producer, with 68% of the world’s supply being extracted within its borders.

The shiny substance is used in steel production, as well as in the chemical industry. It is also the most important ingredient in semiconductors – so much so that the entire IT industry has been named after it. Silicon is also a key part of making solar panels. Any event that impacts China’s supply of silicon could have severe impacts on the clean energy and electronics manufacturing sectors.