Do you remember what you wanted to be when you grew up?

My five-year old son Remy has a classic answer for many little boys: He is adamant that he wants to be a firefighter. This is perhaps on me, since I introduced him to Fireman Sam to keep him occupied during my work calls. It’s too early to talk to him about occupational safety, injury risks and long-term earnings and savings. But thinking about his future makes me wonder, what will a secure job look like moving forward?

A new study commissioned by Consultative Group to Assist the Poor takes a fresh look at how financial services contribute to livelihoods and reframes the argument for productivity, including how to help people do more with the resources they have.

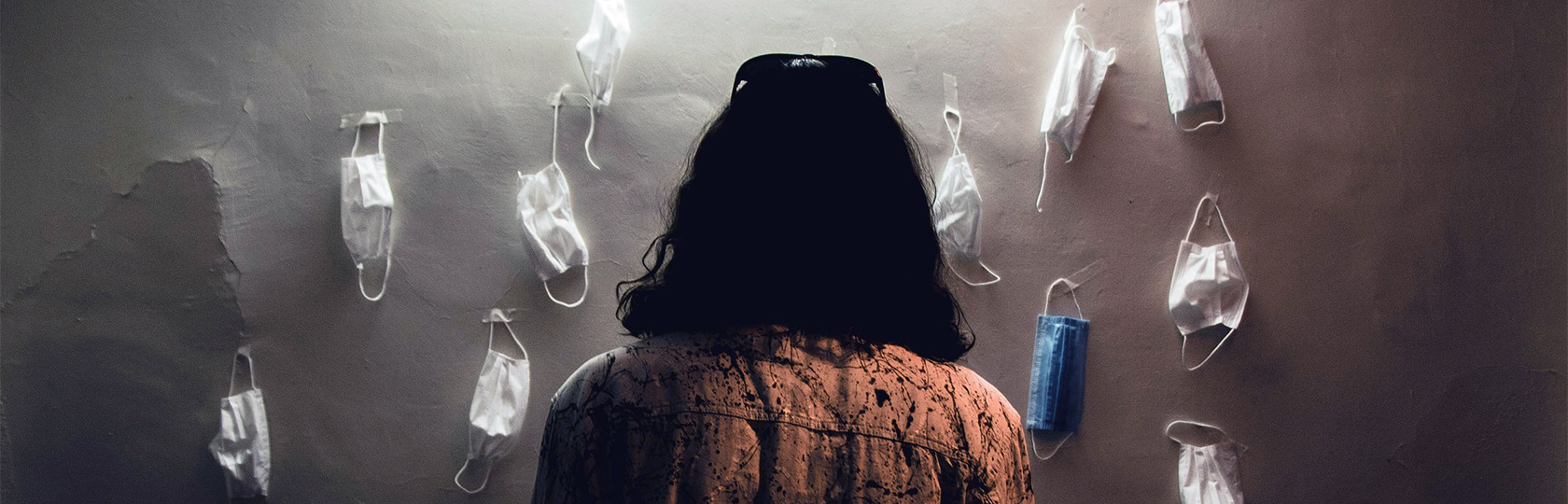

This is an acute concern, where the fallout from COVID-19 has caused striking shifts in the type of businesses and the nature of job occupations most likely to survive. While micro and small businesses have been a major source of livelihoods, for owners and employees, the study finds that micro-enterprises have limited ability to absorb growth funding and turn greater profits.

The authors of the study challenge us beyond providing credit to answer the question, “How can basic management tools related to inventory, physical space and mobile-centric customer management link to financial services and lead to greater productivity gains in these areas?”

McKinsey & Company recently released a report that up to 25% more workers than previously estimated will have to switch occupations due to permanent job losses. It studied the economic and labor markets in eight countries (China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Spain, UK and the U.S.) which account for almost half the global population and 62 percent of global GDP.

Researchers divided job categories by the need for physical proximity, as well as by effects of automation and other technology advancements. In a significant shift, McKinsey predicts greater losses in low-wage jobs rather than the middle-wage jobs. It expects the largest negative impact of the pandemic to fall on workers in food service, customer service, and office support jobs; whereas the biggest increases will come in high-wage, high-skill jobs such as STEM, health, business/legal, and management. Job increases in warehousing and transportation are unlikely to offset the losses in low-wage, low-skill jobs.

The main takeaway here is that low wage earners and small enterprises are the crux of the essential, yet most vulnerable components of U.S. economies. The pandemic has exposed how much we depend on them, and how little their essential work is financially valued and rewarded through salary compensation and benefits.

Small enterprises of fewer than 20 employees are proven job creators relative to small and medium sized enterprises and large corporations, even if they have the smallest share of aggregate employment. They are often the most resilient.

As CEO of Vitas Group, A Global Communities Enterprise, I have been setting up and managing companies who serve these hardworking employees for over two decades. I use the word resilience in microfinance and the global development industry to both describe our clients and to define what we aspire them to be.

Microfinance clients have a long and proven track record of weathering many shocks and overcoming obstacles. Despite cycles of political turmoil, economic recessions, absent government, hyperinflation, and currency devaluation, Vitas’ clients in Lebanon and Iraq continue to run their small groceries, bakeries, and car repair shops.

But this word “resilience” doesn’t really get at it. The essence of so many individuals I have met, some clients and some not, are people who just persevere no matter what. They are people whose resolve and character never see failure as a permanent situation.

My mom called me recently to tell me my great uncle Dan died at 96, just a day after his sister, Mildred, died at 91. The word I’d been searching for immediately came to mind: Grit.

Grit is an Old English word ‘greot’ meaning dust, earth or gravel. To have grit means to have courage and resolve, strength of character. In psychology, grit is “a positive, non-cognitive trait based on an individual’s perseverance combined with powerful motivation to achieve a long-term goal or end state.”

One of the reasons I have been drawn to the microfinance industry for so many years is a profound respect for people who have grit. My late great uncle Dan was the most successful of his 13 siblings, seven brothers (including my maternal grandfather, the oldest) and six sisters.

They were poor and rural farming families drawn to the promise of jobs around Mill Towns established in the South as part of the textile industry at that time. Every one of the brothers had to eke out a living on their own and so most all of them started a business.

My grandpa learned to cut hair at age 12 and at age 19 started working at a barbershop, which he later owned and where two of my mom’s brothers still work as barbers. But Dan was the most successful, going from trading cars, to owning a used car lot, to real estate development.

In my microfinance career, I am working for and with some of the grittiest people on earth. Each one of us has some essence of grit, whether it runs in your family or not. Living in a global pandemic that only comes every 100 years or so, there is no precedent in our lifetimes. But I see my aunts and uncles living well into their 90s who have seen a whole lot in life and are just taking it in stride. There is something to learn from that—the long view.

The long view in finance means it is necessary to accelerate how to redesign and deliver financial services to more small businesses at scale, with heightened attention to productivity, skills retooling, and increasing customers’ knowledge and use of rapidly changing digital ecosystems.

Digital transformation is essential to any executive’s business strategy today. But it is just as important for them to enable their clients and their wage earners to move into the future. It challenges them to rethink how to recruit, manage and retool teams.

The future of work after COVID will force everyone to think about career pathways for themselves, their clients, and the next generation. Who knows what career paths might open up for Remy in 15 or 20 years. He has to time to think and prepare for that. But for now, business, government, non-profit leaders and policy makers, need to face the challenges, seize opportunities and make the future of work happen.