The following is an excerpt from SMIRK, a memoir of journalist Christie Smythe's unusual relationship with "Pharma Bro" Martin Shkreli. It should be viewed as opinion. You can read more at www.smirk-book.com.

So it wasn’t my finest moment…but in the grand scheme of things, looking plainly at what happened, can you really say what I did was all that bad? I didn’t lob any insults. I didn’t violate any Twitter rules, or any professional social media policy that I’m aware of. I didn’t even say anything cruel or negative in the tweet.

At worst, it was a hopelessly awkward attempt to initiate a dialogue with a much more well-known media person than myself about an ongoing public drama that she likely had no desire to discuss with me. But wasn’t Twitter meant for having provocative discussions? At least, that was my operating assumption.

A number of factors contributed to it ending up so weird: At the time tweets were limited to 140 characters, so I didn’t have much space to explain myself very well. Meanwhile, I also wanted to make sure I got her attention. Her social media following was exponentially larger than mine, and I figured the more likely outcome was that I would be ignored.

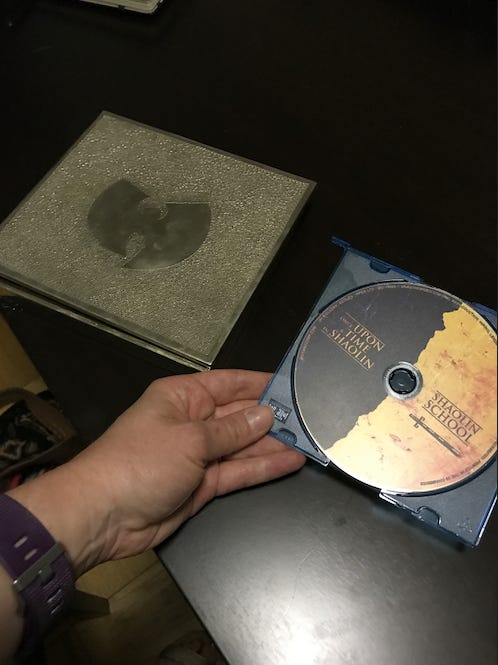

If at all possible, I also wanted to keep it light and mildly funny. (Although that turned out to be a pretty bad tonal error.) I packaged my punchy message with a photo I knew would attract engagement: of me, holding the famous single-copy Wu-Tang Clan album, Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, the musical work the hated "Pharma Bro" Martin Shkreli had purchased for $2 million.

The actual tweet appears to have been lost in the great dustbin of the internet, and that’s probably not a bad thing. But its contents were accurately reported in the Elle profile of my relationship with Martin which went hugely viral in December 2020. The tweet, posted in late July 2017, said: “I don't think [Martin Shkreli] would hurt a woman, even a journalist. Behold me and the #wutang album.”

And I tagged the writer Martin had been kicked off Twitter for harassing earlier that year: Lauren Duca.

Where it began

Lauren Duca was a liberal political writer for Teen Vogue whose star rose enormously following the election of former President Donald Trump — especially after she authored a poignant column accusing him of “gaslighting America.” Her brand of loud feminism and acerbic attitude on social media, where she attacked targets regularly in the name of social justice causes, allowed her to build a base of tens of thousands of impassioned fans.

In August 2016, she also showed up at an impromptu media gathering Martin had thrown together (as some sort of attempt at earnest conversation) at Guy Fieri’s Flavortown Kitchen in Times Square — a restaurant that also been sort of “canceled,” in effect, by a vividly scathing 2012 review in the New York Times. Rather than talk to Martin, however, Duca apparently simply showed up, took a photo of him and posted it on Twitter with a snide comment.

Months later, Martin more discreetly returned the favor. He had been invited to Trump’s inauguration. In a cheeky yet benign direct message on Twitter, he asked if she wanted to be his “plus 1.” Her reply was not discreet. She tweeted a screenshot of his DM, and commented that she would rather “eat” her “own organs.”

Obviously hurt by being so visibly scorned, but pretending like he was not, Martin doubled down…and began crafting a facetious narrative on his Twitter and during his live streams that he was hopelessly in love with her. (Did this make me jealous on a subconscious level? Probably, although I definitely wasn’t admitting that to myself then.)

Naturally, this perverse reaction led to nothing good. His cabal of internet fans and friends encouraged his behavior — making it into a sort of twisted inside joke that was also unfolding, publicly, before a wider audience which found it horrifically offensive. (People acting offended just made the joke funnier to the cabal, which included a fair number of characters who were prone to “trolling” women on the internet.)

The unforgivable act

In January 2017, one of Martin’s friends (a woman) created some gifts for him: They included a photo of Duca cuddling with her then-husband, and Martin’s face was Photoshopped into the image where the husband’s head would have been. She also provided a weird photo collage dedicated to Duca. Martin happily accepted the gifts and used them as his profile photo and Twitter background. Shortly after that, Duca tweeted a complaint about Martin’s Twitter, tagging Jack Dorsey, then the CEO of the platform. Martin was immediately banned for harassment.

If it were possible for Martin to become even more of a pariah, after the scandal over his drug pricing tactics at Turing Pharmaceuticals, and then his arrest on securities fraud charges, getting kicked off Twitter for sexual harassment did it.

Some business journalists I later spoke to told me they had been considering hosting Martin for a panel discussing the issue of prescription drug prices, but they dropped those plans immediately after the Twitter suspension. A talk he had been scheduled to give at Princeton was also canceled — although he ended speaking there anyway a few months later after another student group invited him.

During his live streams, Martin continued to ramble and make cracks about Duca. The pattern started to remind me of Donald Trump’s endless and pointless-seeming attacks on a favorite hobby horse, comedian Rosie O’Donnell, which to anyone observing appears pathetic. Journalists seemed to play along with this narrative, too, suggesting that the whole harassment episode was started when Duca “rejected” Martin (ignoring the context of her randomly mocking him online before that).

As a woman, Martin’s comments bothered me, because regardless of whether Duca was being harmed at all, he was emboldening sexist trolling of all women on the internet by doing it over and over again. I could see he was also hurting himself far more than he was “getting back” at Duca for however much she had embarrassed him.

As his friend, which I was becoming after getting to know him in a professional context, I couldn’t stay silent: “Do you have to keep saying stupid sh*t about Lauren Duca???” I blurted out to him over email in 2017. He didn’t reply.

Sick to my stomach

In late July 2017, Martin’s securities fraud trial was drawing to a close. Showing a display of over-confidence that was typical for him, he began talking on his live streams about how certain he was that he would be acquitted. (He ended up convicted of three of eight charges relating to securities fraud at hedge funds he founded, and was sentenced to seven years in prison.)

In his rising exhilaration, he began to also wrap Duca into his fantasy — declaring that after the whole mess was over, that he would get to “f*ck” her. He meant that she would fall in love with him in this absurd imagined scenario, not that he would have sex with her against her will, he clarified to me later.

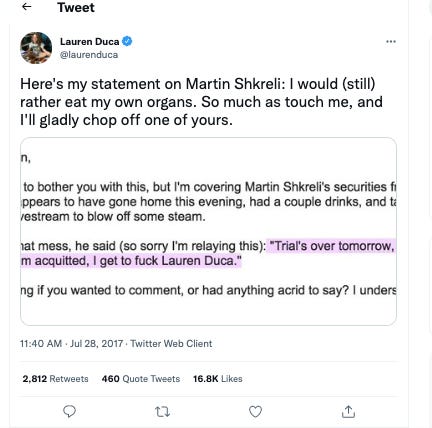

Critics who were listening to him then, though, immediately interpreted his comment as “rape.” A journalist reached out to Duca for comment about it. Her response, posted publicly on Twitter, was predictably searing. “Here's my statement on Martin Shkreli: I would (still) rather eat my own organs. So much as touch me, and I'll gladly chop off one of yours.”

When I saw it, I was sitting at a computer in the press room in Brooklyn federal court. I was still employed as a legal reporter for Bloomberg then, although I was on leave to work on a book about Martin. My heart pounded when I saw the whole thing: Martin’s vulgar comment, the way it was characterized by the reporter who reached out to Duca, her threat of violence in reply, and so many people cheering her on for it. It made me sick…nauseated, even.

I started to think: If only she knew what Martin was really like in person….a shy, passive nerd who was never violent…surely, that could make some sort of difference in this whole unholy exchange? It was a stupid thought, but it stayed firmly planted in my brain. At last, I couldn’t help myself. I posted my ridiculous Wu-Tang album tweet.

Swift response

For better or worse, I succeeded in getting her attention. “F*ck you,” she replied swiftly. (And then just as quickly she deleted her comment.) Soon I was at the bottom of a dogpile (a place that would become familiar to me) condemning me for “attacking” her and supporting her “abuser.”

My soon-to-be ex-husband jumped on board, too. He sent me a barrage of angry emails, filled with biting comments that would serve as a preview for how Twitter reacted when I later became Martin’s girlfriend.

He declared that I was “off” my “rocker” and was committing “career suicide.” “PERCEPTION IS REALITY,” he added. “You can’t change that.” He demanded that I delete the tweet, and then when I refused, told me he would divorce me over it. (We stayed married, though, until roughly a year later.) He insisted I was siding with everything terrible in the universe, and praising bullies who hurt women, and that I should be “ashamed” of myself.

All because I tweeted a picture of an album and tagged Lauren Duca. That was enough to make me a villain now. I was stunned.